A headline that feels like a bad memory

The words Chernobyl and radiation still press on the world like a bruise. Now we read that the giant steel shield over the ruined reactor has “lost its primary safety functions” after a wartime drone strike. The warning comes from the UN’s nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency, usually called the IAEA.

Radiation levels around the site remain stable for now. There is no new leak. The old concrete sarcophagus that covers the core is still in place. The danger today is not an instant replay of 1986. The danger is slow damage that makes the site weaker and more fragile over time, especially in an active war zone.

As we walk through what happened and what comes next, we keep one idea in mind. This is not just a Ukrainian story or a European story. It is a reminder that nuclear accidents do not stay inside national borders, and that war and nuclear sites never mix safely.

A short reminder of what happened at Chernobyl in 1986

In April 1986, Reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded during a late-night test. The blast and fire threw out huge amounts of radioactive material. A crude concrete and steel “sarcophagus” was built in a rush over the broken reactor to trap radioactive dust and debris.

That first shelter was never meant to last forever. It cracked, leaked, and began to sag. Engineers knew that something stronger and safer had to replace it, or the ruins would slowly crumble and release more contamination into the air and soil over the decades to come.

The answer was a new structure, planned on a massive scale.

The New Safe Confinement, the giant arch over the ruins

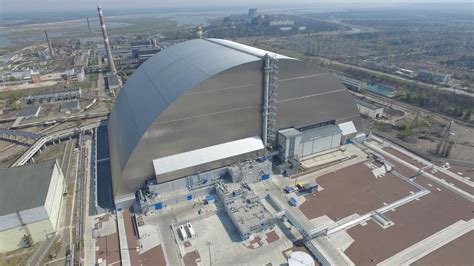

The huge steel arch that most of us picture when we think of Chernobyl today is called the New Safe Confinement, or NSC. It is one of the largest movable structures ever built. Engineers assembled it next to the reactor site and then slid it into place over the old sarcophagus.

The NSC was finished and put into service only a few years ago. It cost around €1.5 billion and was designed to last about 100 years. Its job was simple to describe and hard to do. It had to keep rain and snow away from the ruins, trap any radioactive dust inside, and create a safe workspace for crews to dismantle the old shelter and manage the deadly materials below.

In normal times, this arch would have quietly done its work in the background while the world slowly forgot about it. These are not normal times.

How a wartime drone pierced the shield

In the night of February 13–14, 2025, a drone carrying a high-explosive warhead hit the NSC. Ukrainian authorities said the drone was Russian and accused Moscow of a deliberate strike on the shelter. Russian officials denied responsibility. The IAEA has not formally assigned blame to either side.

The blast did not punch straight into the radioactive core. Instead, it tore through the outer cladding of the arch over a technical area, damaging inner layers and setting the insulation on fire. Workers had to fight the fire in bitter winter cold while smoke and heat hid the flames deep inside the layers of the roof. Repairs began quickly, but they were limited. The focus was on stopping the fire and closing the obvious breach, not on a full rebuild.

From the outside, life seemed to go back to normal. Radiation readings stayed within expected ranges, and there was no sign of a major leak. Inside the structure, though, the story was more complex.

What the IAEA says today about the damage

Months after the strike, an IAEA team inspected the NSC in detail. Their new report is the source of the headline that caught our attention. The agency says the New Safe Confinement has “lost its primary safety functions, including the confinement capability.” In simple words, the arch no longer does its full job as a barrier against radiation.

At the same time, the IAEA stresses three important points.

- The main load-bearing structures of the arch are still sound

- The monitoring systems are still working

- Radiation levels at and around the site remain stable, with no new leak detected so far

The problem sits in the damaged shell, the layers meant to seal in dust and protect the inner parts from weather and more shocks. The structure is now more open to rain, snow, corrosion, and future attacks. The IAEA calls for “comprehensive restoration” and warns that waiting too long raises the risk of further deterioration and higher repair costs.

The real-world risk right now

For people living in Ukraine and across Europe, and even for those of us far away, the natural fear is a repeat of the old nightmare. The picture today is different.

The broken reactor core remains wrapped in the old concrete sarcophagus under the arch. The recent strike did not smash through that inner layer. Radiation measurements around the plant are still normal. Officials and independent monitors repeat the same basic message. There is no sign of a new, active release from the reactor ruins right now.

The danger lies in what could happen if the damaged shield is not fixed or if another strike hits the same area. The arch was built to keep long-lived radioactive dust from escaping as the old shelter ages and is taken apart. If the NSC weakens further or collapses over time, wind and rain could reach materials that should stay sealed, and workers would face a much more hazardous environment.

So the risk is not an instant explosion like 1986. The risk is a slow slide into a situation where a future shock, fire, or attack could send radioactive dust into the air again.

Why nuclear sites in a war zone are so fragile

Chernobyl is not the only nuclear site under pressure in this war. The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the largest in Europe, has lost its last external power line many times during repeated shelling and missile strikes. Each time, reactors and cooling systems have had to rely on backup diesel generators, and each time experts remind the world that this is not a safe way to run a nuclear site.

Nuclear plants are built for many kinds of accidents, but they are not built to be battlefields. Power lines can be cut. Control rooms can be shaken by explosions. Firefighters can be blocked by active combat. A drone strike, even one aimed at “only” a roof or a support building, can start a chain of events that designers never fully planned for. The NSC at Chernobyl was designed to resist storms and time, not birds of prey made of metal and explosives.

When war enters the picture, every layer of safety becomes thinner.

The money, the repairs, and the politics

Major repairs to the Chernobyl shield will be expensive. Early estimates suggest tens of millions of dollars, and some Ukrainian officials say the final bill could reach or even pass €100 million. Funding is likely to involve the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and other international partners, just as the original arch did. (Wikipedia)

Ukraine argues that Russia should be held responsible for the damage and the cost, since it blames Moscow for the drone strike. Russia denies it carried out the attack. The IAEA, as a technical body, avoids taking sides and focuses on the condition of the structure itself and on the need for protection and repair.

The result is a familiar pattern. The people living with the risk need quick action. The engineers know what to do. The politics and the money move more slowly.

What the world can do to reduce the danger

Nuclear safety in wartime rests on a few clear steps.

First, all sides need to treat places like Chernobyl and Zaporizhzhia as off-limits for attacks. The IAEA has pushed for special safety and security zones around nuclear sites in Ukraine. The idea is simple. No weapons, no military units, no strikes in or near these sites. The practice has been much harder to achieve. (IAEA)

Second, repairs at Chernobyl need to move from short-term patches to full restoration. That means sealing damaged cladding, replacing burned insulation, checking internal supports, and making sure drainage and corrosion-control systems still work as designed. Each year of delay makes the job bigger and the risk higher.

Third, independent monitoring has to continue and even expand. Long after the headlines fade, sensors and sample teams will watch radiation levels, structural movement, and air quality around the site. Those numbers provide the early warnings that keep a bad situation from becoming a disaster.

What this means for you and me

From a distance, it is easy to feel helpless. The war is far away. Nuclear engineering feels complex. But this story touches the daily lives of all of us in quiet ways.

We share the air and the climate with people in other countries. A large nuclear release in Ukraine would not respect borders. It would move with the wind and the rain. It would creep along food chains and across trade routes. Keeping sites like Chernobyl safe is a shared task, not a local chore.

This story also reminds us that the cost of war is not only in lives and ruined homes. It is also in the slow wear on infrastructure that was built to protect future generations. Money that goes into repairing a damaged shield could have gone into schools, hospitals, or clean energy projects. Instead it has to be spent simply to hold the line on a danger we thought was locked down.

When we support efforts to strengthen international rules, fund nuclear safety work, or help refugees, we are part of a broader push to limit the fallout of this war in every sense of the word.

Why this story still matters tomorrow

The damaged Chernobyl shield is a warning light on the global dashboard. It tells us that a structure built to keep one of history’s worst nuclear accidents under control is now less secure than it should be. It tells us that modern warfare has reached into places that should never be battlefields. It tells us that long-term safety cannot rest on short-term fixes.

Radiation levels today remain normal. The core is still inside its old shell. The world is not facing a second 1986 at this moment. At the same time, the system that was supposed to hold the danger in place for a century now needs urgent help of its own.

As we move on to other headlines, this one keeps working quietly in the background. Engineers will climb inside the arch. Welders will seal plate to plate. Inspectors will read sensor logs and walk the perimeter in snow and rain. If they succeed, most of us will never hear about it again.

That quiet success is the goal. A stable Chernobyl shield means less risk for Ukraine, for Europe, and for all of us who share this planet.